Lack of FIRs coupled with weak prosecution laws keeps cybercriminals on the loose

By Manas Pimpalkhare | January 6, 2024

The possibility of seeing nude pictures of himself on the internet for defaulting on a loan worried Ravindra Lombte, a 42-year-old driver from Beed in Maharashtra.

Lombte, in October 2023, saw an advertisement for a loan app on Facebook, and borrowed Rs. 2,025 after submitting a proof of identity. He was asked to repay Rs.3,100 in six days, which he promptly repaid. Wanting to send money back home to his family, Lombte borrowed from the same app again. On borrowing Rs.5,575 the third time around, he was unable to repay it on time.

“If I did not repay the loan, they said they would send nude pictures of me to my family,” said Lombte. He was told to make payments of Rs.3,219 every six days to keep the pictures from going viral. “I will have to keep doing this until I can pay the full amount with interest in a single transaction,” he said.

Lombte went to a police station to report the case. “The police did not register my complaint,” he said. “And instead asked me why I used this loan app to borrow money.”

Among the complaints that do get registered by the police, the number of cases that reach courts is far lower. In 2022, Maharashtra reported 8,249 cybercrime cases, according to the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB). In the same time, Maharashtra’s cyber police stations filed only 78 FIRs, according to the police’s Crime and Criminal Tracking Network & System (CCTNS) portal.

This shows that Maharashtra police, responsible for tackling cybercrime in India’s richest state by gross domestic product (GDP), is struggling to fulfil its mandate, breaking the current central government’s 2019 promise of reducing cybercrime.

This huge gap between the number of cases and registered FIRs points to lapses in the government’s policy on reducing and prosecuting cybercrime. Maharashtra police handles over a thousand complaint calls on the cybercrime helpline every day, but the number of cases that enter courts is far lower, despite the central and state government’s aid in modernising the police.

The Ministry of Home Affairs (MHA) allocated a part of its Rs.36.24 crore modernisation budget to tackling cybercrime in Maharashtra. It has also allocated Rs.340 crore in its 2022-23 budget to the Indian Cyber Crime Coordination Centre (I4C), a national body to detect cybercrime.

These measures, however, fall short of actually taking action against the issue. A National Cyber Forensics Lab set up under the I4C has helped law enforcement agencies in 5,800 cybercrime cases, said the MHA in its annual report for 2022-23. This is only 8.7% of all cybercrime cases recorded in 2022, according to NCRB data.

While the government’s policies against cybercrimes stop at speedy detection and raising awareness by allowing people to file a complaint on a cybercrime portal without filing an FIR, the problems for victims only begin there.

Mohsin Khan, a 35-year-old lawyer in Pune who was representing a victim who had made an online complaint of cyber fraud but not filed an FIR, was stumped when he tried to recover stolen funds. His client had lost Rs.1.19 lakh in December 2023, and the police had managed to recover 80% of the money.

The money had been returned to the court, and Khan needed to file an application to secure the funds and transfer it back to his client. He could not file an application without an FIR number. “Not filing an FIR is the difference between the victim getting their money back and losing it all,” he said.

Cybercrime victims do not register the crime because they have to report it to a police station, and follow the court’s procedure, said Sadanand Date, head of Maharashtra Anti-Terrorism Squad. “If people are given a shortcut to getting their money back, why would they take the longer route?” he said.

In cases where police investigate and nab accused persons based on an FIR, it is difficult to prosecute them, said Gajanan Kadam, Inspector, Navi Mumbai Cyber Police Station. The Information Technology (IT) Act used to prosecute cybercrime has kept most crimes bailable, he said.

To keep the accused from getting bail, the police have to attach provisions from other penal laws in their chargesheets. We have to use the legal provision for cheating in cyber fraud cases because that is a non-bailable offence, said PSI Sandip Kadam in the Pune Cyber Police Station. “We have also used special laws like the penal laws against organised crime in our chargesheets,” he said. “At least they will stay in jail for some time.”

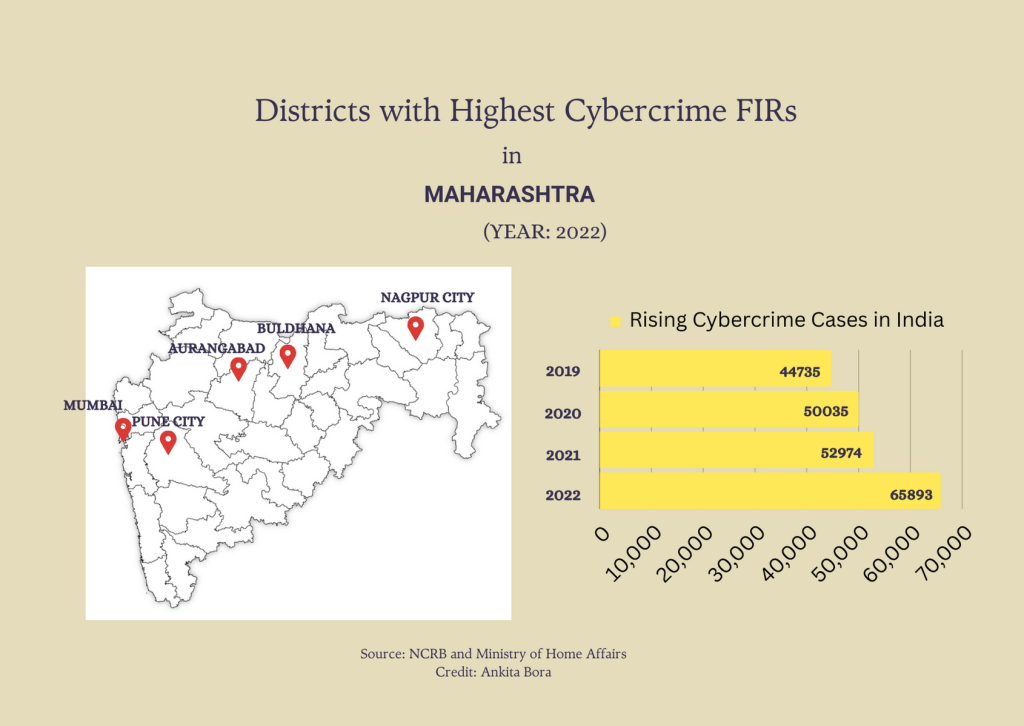

The number of cybercrime FIRs that are being registered is a very minuscule percentage of the total number of cases, and the conviction rate is less than 0.1%, said Pavan Duggal, a cyber law expert and practising advocate in the Supreme Court. Cybercrime cases in India rose 32% to 65,893 in 2022 from 44,735 in 2019, as per MHA and NCRB data. In metropolitan cities, cybercrime cases in 2022 jumped 42% to 24,420 from the year before. “We have to realise that post COVID-19, the golden age of cybercrime has begun,” said Duggal.

The lack of manpower in the police force assumes importance as cybercrime cases rise every year. Take the case of Pune, which has one cyber police station handling cases valued over Rs.2.5 lakh. This is the only cyber police station for the district, which had a population of over 94 lakh in the 2011 census.

All cases filed in this police station are investigated by two inspectors, the only ones authorised to investigate. These two inspectors have to go out twice or thrice every week to speak about cybercrime and raise awareness. They also have to go out for field work, while handling 80 investigations at once. “Who do they think we are, Rajinikanth?” said PSI Sandip Kadam, Pune Cyber Police Station.

The central government conducts training programmes to sensitise police officers, lawyers, and judges in handling cybercrime cases. The MHA has trained 4,292 officers across India in cybercrime investigation techniques, according to its 2022-23 annual report. It also states that 29,945 officers and other stakeholders went through training in 2022-23, a part of which was about cybercrime. These training and capacity building policies impact only a small part of the country’s total police force, which has over 26 lakh sanctioned officers.

More capacity building amongst the police and law enforcement agencies is the need of the hour, said Duggal. “Much bigger budgets are required,” he said about the Modernisation of the Police Force Scheme.

The gaps in detection, investigation, and prosecution of cybercrime have forced Ravindra Lombte to fall into a vicious cycle of debt. He had to borrow Rs.25,000 from his employer to repay the initial debt and keep obscene pictures of himself away from the internet. His complaint, however, has still not been recorded.