By Khushi Malhotra | January 7, 2024

Shelter is a fundamental right, but not all are eligible for it in the capital. A 63-year-old, Ganga Devi, moved to the city in the 1980s when the former Prime Minister Indira Gandhi promised land to the landless laborers in India. Devi and her husband received a forested wasteland in Delhi’s Kalkaji and turned it into a home with their bare hands.

Today, she lives in the shattered remains of the Bhoomiheen camp at Kalkaji, the first slum complex to receive flats under the 2016 Slum Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy of the Ministry of Urban Affairs. Ganga Devi was one of many that were considered ineligible for rehabilitation and continues to live in rubble of what she built 40 years ago.

Devi now lives with her sick son in a half-broken house. Every day, she walks over the ruins of plundered homes — a debris that can cut through slippers or twist her ankle — to fetch water from the remains of a water connection pipe.

In 2015, Prime Minister Modi announced a national goal to provide “housing for all” by 2022. The policy required people to be on at least one of the voters’ lists from 2012 to 2015 and compulsorily in the survey year 2019, among other things.

“My children were born here, married here, and now they are all around 40 years old. We were all waiting for the house promised by the government,” Devi said. “For one vote, they cancelled my house. What was my fault that my name did not come up in one voters’ list?”

Modi wasn’t alone in his promise to build homes for the squatter population. The Chief Minister of Delhi, Arwind Kejriwal, also included In-Situ Slum Rehabilitation in his 2015 manifesto.

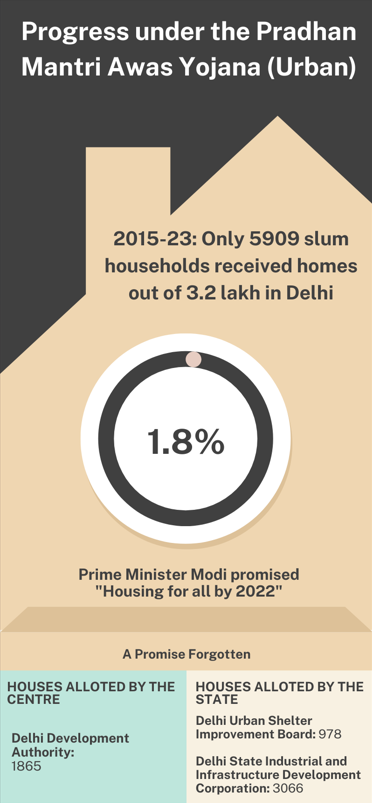

Eight years later, less than 1.8% slum households received homes in New Delhi, including flats made by both center and state. There are over 3.2 lakh recognized slum households in the capital, according to a 2020 report by the Indian Institute for Human Settlements.

In November 2022, almost a year after the deadline, the Modi government inaugurated Delhi Development Authority’s (DDA) first completed slum rehabilitation project, including 3024 flats at Kalkaji for the Bhoomiheen camp. Only 1865 families were allotted homes, while the rest were not considered eligible due to missing documents, a senior official at DDA, who looked at the project closely, said on the condition of anonymity.

The DDA conducted eligibility surveys after the flats were made, the official said. “We conducted surveys in a way that the number of eligible people were equal to the number of flats.”

The central government had built houses for the slum dwellers under the Pradhan Mantri Awaas Yojana – Urban (PMAY-U). The PMAY website claimed that 29,976 flats have been built so far for all categories.

Out of this, 4044 houses were given to slum dwellers, according to data by the Delhi Urban Shelter Improvement Board (DUSIB) and Delhi State Industrial Infrastructure Development Corporation (DSIIDC).

The total flats include the ones built under the Jawaharlal Nehru National Urban Renewal Mission (JNNURM) scheme; a project started by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA).

The rest of the houses built under JNNURM are abandoned, empty and in poor condition, Chief Engineer at DSIIDC, S.N. Sharan, said.

In 2021, Modi instructed the DDA to construct houses for 10 lakh slum dwellers as per the Delhi Master Plan. The DDA floated 10 tenders for building over 22,000 flats, but the projects were eventually cancelled due to no response or contractual issues with developers, according to documents seen by The BottomLine.

“We had many rounds of meetings with the Delhi Development Authority. In a couple of bids, we were the only bidders,” the Chief Executive Officer of a key developer Prabhatam Group, Rakesh Sharma, said. “Finally, they cancelled the tender itself without communicating the reason for cancellation.”

DDA has only three ongoing projects now: Kalkaji, Jailorwala Bagh and a 9-year-old project at the Kathputli colony.

Delhi has the lowest ratio of houses demanded to houses sanctioned in the country under PMAY with only 32% flats sanctioned under the scheme, according to a February 2023 statement by the Press Information Bureau.

Some experts doubt the success of PMAY throughout India.

“They claim success but as far as administration is concerned, it is dependent on just saying that we have built so many houses and then allotted it,” a leading social scientist and expert on land management, Anubrotto Roy, said. “Nobody goes back and checks whether people have actually stayed. There is a problem of data credibility.”

Roy, who is also the Director of Hazards Centre (New Delhi), said that claims of the success of this scheme are going to be an important marker in the upcoming elections.

Before G20, at least 49 demolition drives were conducted in New Delhi, where nearly 93 hectares of public land was reclaimed Kaushal Kishore, the state minister for housing and urban affairs, said in the parliament in July 2023.

The failure of the PMAY scheme in Delhi has brought together at least 250 slum dwellers in Kalkaji to form the ‘All India Group’, an association that moved to court against the government.

“We have filed a case in Delhi High Court because the policy is unfair and disregards uneducated people like us,” the group’s leader, Mohammad Aneez said, who is handicapped and runs a small grocery shop. He has 18 members in his family, living in 10 by 10 units one over the other, which is about the size of a single-car parking space.

“Ours was the first family rejected under the policy,” said Aneez. The policy said that to be eligible, people on each floor should have separate ration cards, “We live in a joint family, we never had different cards,” said Aneez.

On the state front, Kejriwal had promised 78000 flats under the scheme in a speech in 2022, and not a single flat has been built under it. Since 2020, DUSIB received only Rs. 2 lakhs each year for slum, the Principal Commissioner of DUSIB, rehabilitation, according to DUSIB reports. No flat has been made within a 5 km radius of the slums, P.K Jha, said.

The central government stopped funding DUSIB after Kejriwal renamed PMAY to MMAY: Mukhya Mantri Awas Yojana, said the DDA official.

This political tussle has prevented DUSIB to allot any of the JNNURM flats to slum dwellers. In fact, these homes will now be used under a new scheme called the Affordable Rental Housing Complexes Scheme (ARCH). This means that a majority of the flats built so far will not be given to slum dwellers rent free, Jha said.

The union minister of Housing and Urban Affairs, Hardeep Singh Puri, and the state minister, Kaushal Kishore did not respond to emails.

The Slum Rehabilitation and Relocation Policy, 2015, has set several other eligibility criteria such as the slum cluster should be older than 2006 and the houses should not have been built after 2015.

The ones that have received the flats at Kalkaji, however, are also worried about losing their homes due to policy clauses.

The policy states that if any slum dweller is found to have another flat registered in their name anywhere in India, their housing privileges can be taken away.

“The policy meant different things in Hindi and English,” a member of the All India Group said as he pointed out words from the policy. “When we finally understood it, we couldn’t sleep at night.”

“My house is registered under my grandfather’s name, who came here 50 years ago,” the member said. “If he had a house in his village before he came here, my family would not get a home in Delhi, where we were born and worked our whole lives.”

While the slum rehabilitation policy stemmed from the idea that hawkers and vendors should be able to live close to where they work, the implementation of the policy and its clauses has put a question mark on the future of both the homeless and the beneficiaries.

“Where in the policy is it written that we had to vote in all these years?” the member said.

As correctly identified by the member, the 2016 policy said that the name of dweller must appear in “at least” one of the voter’s lists and not all like the DDA told Ganga Devi.

Devi is now relying on the court case by the All India Group, which helped get a stay on her house. If they lose, her house too will be demolished. “Where will I go then? We don’t have a house anywhere else in India,” she said.