“Wash.”

The person serving food at Mylapore’s Karpagambal mess said, looking at the banana leaf spread out on the table. While this may be regular for the average South Indian at a typical Tamil eatery, to others it is a glimpse into the messes of Chennai. He put water on the leaves, directing that it needed to be wiped clean before he placed a ghee roast dosa and a spoonful of podi, a coarse spicy dal powder, on the plantain leaf plate.

As daunting as these small, low-cost family-run eateries or “messes” may be for first-time visitors, people in Chennai swear by them.

Surviving a Pandemic:

The messes were shut for about 6 months during the COVID-19 lockdown. The workers, mostly migrants, went back home. They got either a month’s salary if they worked at Kasi Vinayaga Mess, or financial support throughout the lockdown if they worked at Karpagambal Mess.

“When I earned more, I didn’t give them extra,” said S Prabhu, Karpagambal Mess’ owner. So when he didn’t earn, he didn’t stop their payment. He mentioned that one of his workers had a baby girl one day before the lockdown. Another got married. He had to support them through the lockdown, he said.

It’s one of the bigger messes in town, with Prabhu owning the entire three-storeyed building.

The Fishermen’s Mess, which overlooks the Bay of Bengal from Marina beach, is a family-run venture. The owner M Rajesh’s mother cooks the meals, with help from his aunts. They’ve been able to go back to only 50% of pre-pandemic business as of February 2021, with Rajendran estimating that it would take three more months for business to fully recover.

He goes out fishing every morning with his family, from 2 a.m. to 5:30 a.m., an activity which was banned during the lockdown.

“I reduced my family expenses…got a loan against jewellery (to survive the pandemic). We played games and repaired our fishing nets when the mess was shut,” he said. On a usual business day, the family of about 10 people divide the profit amongst themselves and keep money aside for the next day’s purchases for the eating shack. Each person gets about ₹1,000 per day, he said.

Recovery has been slow for Trouser Mess as well. 75-year-old R Rajendran who owns the place, can be seen in his kitchen, where he only wears a trouser while cooking the dishes on a wooden stove, hence earning the eatery its name. They made around ₹10,000 to ₹15,000 daily before the pandemic, down to ₹5,000 to ₹6,000 per day now, he said.

“During lockdown time, I only had 20-30 customers for whom I made food daily. Even though the shop was closed, I cooked and delivered the food to nearby customers,” he said. Bachelors staying around the area got food from his mess during the pandemic. Regulars opted for take-aways.

Wearing a crisp white veshti with an equally spotless shirt, 72-year-old K Vasudevan, who started the Kasi Vinayaga Mess in 1971, spent over half an hour during peak lunch hours, talking to The Bottomline about the pandemic and his business.

He tried his hand at numerous trades–right from running a mechanic’s shop to a footwear shop–before zeroing down on a mess.

“People would always want food!” was Vasudevan’s reasoning.

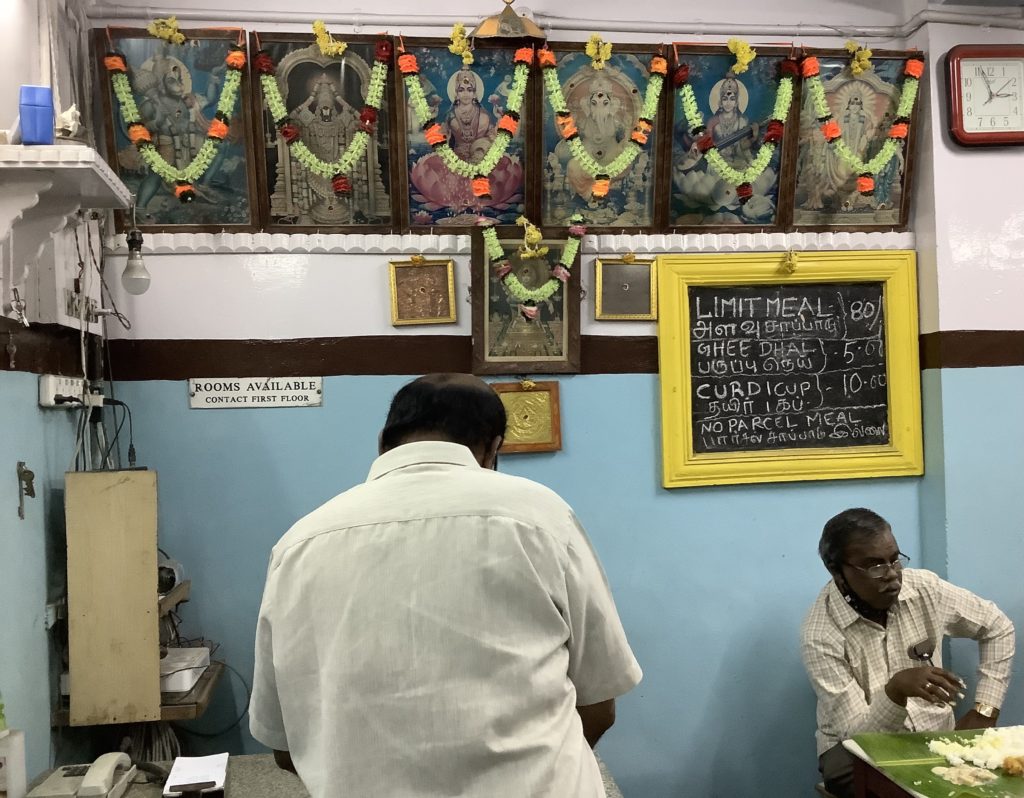

A “limit meal” or fixed meal costs ₹80 at Kasi Vinayaga. A large serving of rice, unlimited refills of two vegetarian side dishes; one dal, or lentil soup; and papadam is laid out on a fresh banana leaf. Vasudevan starts the restaurant at 12 p.m. and gives his staff food to eat first. This helps him understand if the food tastes good, or if it needs more seasoning. For lunch, 300 people come. Back of the envelope calculations indicate that he earns about ₹7,20,000 each month.

He paid to bring his workers back once the lockdown eased.

Vasudevan’s sons insist on expanding the business, a suggestion he always shoots down, keeping his customers in mind. His regular customers comprise only 30% high-class officers, while the rest are middle-class employees.

“Hence, I don’t want to increase the prices,” he said, adding that there were plenty of hotels in the vicinity and he wanted to retain his clientele for whom price matters.

Listen to a podcast on this: